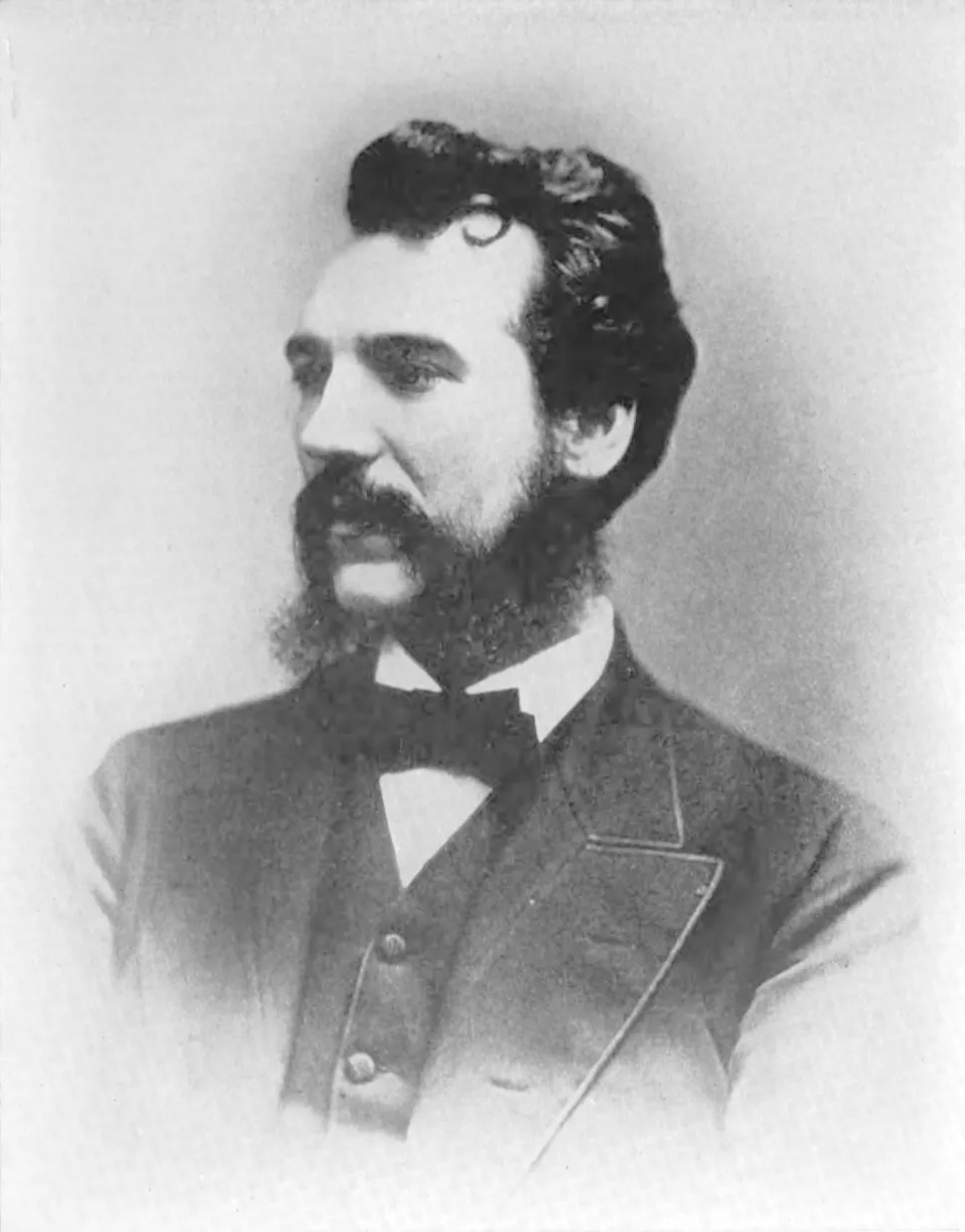

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell was born in 1847 Scotland. His father, also named Alexander Bell, invented a system of "visible speech", wrote books on the art of speaking, and was a university teacher of elocution. His grandfather, also named Alexander Bell, invented a system for the correction of stammering and other defective speech.

Alexander Graham had two brothers, and they were pushed by parents to continue this tradition of studying speech. They were offered a prize to construct a speaking machine. Alexander and his brother used gutta-percha to model a human skull, and india-rubber for the soft mouth parts, stuffed with cotton batting. By blowing air through an artificial larynx, a voice-like sound was heard, that could be manipulated by moving the artificial lips and tongue. With this trick, they could produce some words to be heard. All brothers eventually followed their father with elocution as their profession.

When Alexander was around 18 years old, he became a teacher of music. While there, he experimented with his mouth cavity, to determine the resonance pitches of vowel sounds. He thought this was original research, but found a more sophisticated version had already been done using electromagnets causing resonators and tuning forks of different pitches to resonate. Bell did not understand the electrical aspects, but was inspired to learn. In 1867, he experimented with a telegraph, trying to cause this vibration of a tuning fork using the electromagnets.

His brothers died of tuberculosis, so his father resigned and the remaining family moved to Canada in 1870 with hope of avoiding further death. In 1871, Alexander Graham went to Boston for a couple months, to help a school for deaf mutes try to teach the students to speak using his father's "visible speech" system. He then visited another deaf school for a couple months, then another in Connecticut. In 1872, he moved to Boston, where he opened a school of vocal physiology focused on deaf mutes, defective speech, and teachers of the deaf and dumb.

In 1873, Bell moved to Salem, and was a professor of vocal physiology at Boston University. He experimented with using the electromagnetic resonance combined with telegraphy in hopes of sending multiple harmonic signals simultaneously. He had multiple tuning forks, with the prongs placed between the poles of electromagnets, connected to a paired tuning fork through telegraphic wire. With the use of a battery and telegraphic switch, multiple tones could be relayed across a single wire. It was a prototype for an electric wave filter and carrier method of signalling.

During the winter of 1873-1874, he replaced the receiving forks with tuned reeds, and experimented further. He learned about a "manometric capsule", which was a kind of instrument with a cavity in a piece of wood, divided into two portions by a partition like a diaphragm made of gold-beater's skin. One compartment had a a gas pipe to fill it with gas and lighted with a burner. The other was connected to a speaking-tube, so if you speak into the tube, the vibrations through the air, membrane, and gas caused the flame to vibrate with the voice, so you could see the sound wave. He also learned about a similar instrument called a "phoneautograph", which used a wooden lever and bristle to draw the waves onto smoked glass. These were early forms of oscilloscope.

Bell put all these concepts together trying various designs for how to transmit speech across a wire, and in the summer of 1874, he came up with a membrane speaking telephone, where an instrument similar to the transmitter could also be used as the receiver. His plan was to attach the free end of a reed to the center of a stretched membrane, with a magnetic pole brought close to the hinged end of the reed, to polarize it by magnetic induction. He later used a similar design for a patent in 1876.

In the summer of 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was demonstrating experiments.

Only a few days later another notable event in the history of the electric speaking telephone occurred. Articulate speech was, for the first time, transmitted and received between places that were separated by miles of space. I recall three experiments that were made in Canada, during the first two weeks of August, 1876. In all three of these experiments a membrane telephone was used as a transmitter, and the iron-box telephone as a receiver; and the membrane telephone was located in the office of the Dominion Telegraph Company, in Brantford, Ontario. The iron-box receiver was, in one experiment, located in the town of Paris, about eight miles from Brantford, the battery, however, being in Toronto, a distance of 68 miles from Paris. In another experiment the receiver was in Mount Pleasant, about five miles from Brantford; and in the third experiment, the receiver was placed on the veranda of my father's house at Tutelo Heights, a distance, I suppose, of three or perhaps four miles from Brantford.

In the first experiment alluded to, the membrane telephone with (the) triple mouthpiece was placed in the Dominion Telegraph Company's office in Brantford, under the charge of Mr. Griffin, who was, if I remember rightly, either the manager or operator there. As my father told me he would be unable to be present on account of an engagement, I made arrangements with my uncle, Professor David C. Bell, to go to the Dominion office at an appointed hour, and recite into the membrane telephone. I also requested him to provide some singers, who should sing a three-part song into the triple mouthpiece. I then drove to the town of Paris-eight miles from Brantford-and attached the iron-box receiver to one of the lines leading to Brantford. The battery that operated the instruments was—as I have already said-in Toronto. I had provided electromagnets having coils of different resistance, which could be interchangably used in the telephones employed. Low-resistance coils were first tried. The moment I placed my ear against the diaphragm of the iron-box receiver, I heard bubbling and crackling sounds, similar to those I had observed on the New York loop experiment, made July 12, 1876, on the lines of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company. Mixed up with this storm of noises, I could plainly perceive the voices of the speakers and singers in Brantford, in a faint, far-away sort of manner. I then telegraphed to Brantford by another line; and asked Mr. Griffin to substitute an electromagnet with coils of high resistance for the low-resistance one he had been using. While he was doing this, I made a similar change in the coil of the iron-box receiver. The experiments were then resumed. The disturbing noises still continued, but the vocal sounds, in place of being faint and far away, became so loud and clear that familiar sentences were understood, and I could even recognize the voices of the different speakers and singers. One voice sounded so like my father's that I telegraphed to Brantford to ascertain whether it could possibly be his, for I had understood that he could not be present at the time. He was there, however, and it was his voice that I had heard...

This, I believe, was the first time words and sentences spoken in one place were transmitted by electrical means and successfully reproduced in another place many miles away.

— Alexander Graham Bell